Applied Crypto Highlights: Searchable Encryption with Ranked Results

15/Apr 2015

This is the second in a series of guest posts highlighting new research in applied cryptography. This post is written by Foteini Baldimtsi who is a postdoc at Boston University and Olya Ohrimenko who is a postdoc at Microsoft Research. Note that Olya is on the job market this year.

Modern cloud services let their users outsource data as well as request

computations on it. Due to potentially sensitive content of users' data and

distrust in cloud services, it is natural for users to outsource their data

encrypted. It is, however, important for the users to still be able to use

cloud services for performing computations on the encrypted data. In this

article we consider an important class of such computations: search over

outsourced encrypted data. Searchable Encryption has attracted a lot of

attention from research community and has been thoroughly described by Seny

in previous blog posts.

Modern cloud services let their users outsource data as well as request

computations on it. Due to potentially sensitive content of users' data and

distrust in cloud services, it is natural for users to outsource their data

encrypted. It is, however, important for the users to still be able to use

cloud services for performing computations on the encrypted data. In this

article we consider an important class of such computations: search over

outsourced encrypted data. Searchable Encryption has attracted a lot of

attention from research community and has been thoroughly described by Seny

in previous blog posts.

Search functionality alone, however, might not be enough when one considers a large amount of data. Ideally, users would like to not only receive the matching results, but get them back sorted according to how relevant they are to their query (just like a search engine does!). In this blog post we describe our recent result from the conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security 2015 which builds on top of searchable encryption techniques to return ranked results to users' queries. Our goal is to create a scheme that is efficient and achieves a high level of privacy against a curious cloud server.

Ranking search results on plaintext data

Let us start by briefly describing how ranking would be done if users did not take into account the privacy of their data and outsourced it in an unencrypted format. Literature on information retrieval offers an abundance of ranking methods. For our paper, we chose the $\mbox{tf-idf}$ ranking method due to its simplicity, popularity and the fact that it supports free text queries. This method is effective since it is based on term/keyword frequency (tf) and inverse document frequency (idf).

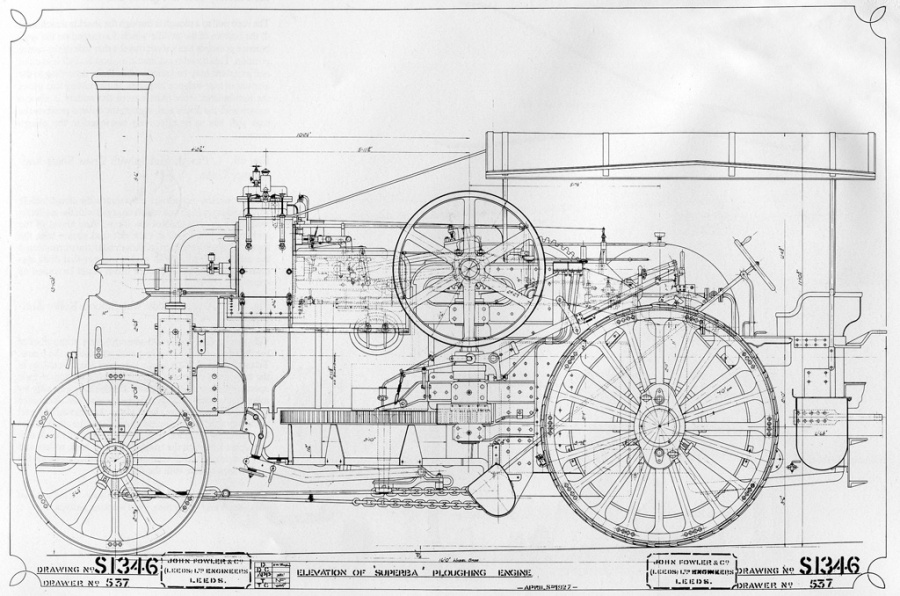

Let $D=D_1,\dots,D_n$ be a document collection of $n$ documents, in which there exist $m$ unique terms/keywords $t_1,\dots,t_m$. First, for every term, $t$, we compute its frequency ($\mbox{tf}$) in each document $D_i$ as well as its inverse document frequency ($\mbox{idf}$) in the entire collection (it captures how common the term is in the whole document collection). Then, for each term and document we compute

\[ \mbox{tf-idf}_{t,D_i} = \mbox{tf}_{t,d} \times \mbox{idf}_{t} \]

and store the score values in the rank table, $T$:

Note that if a term does not appear in a table, then we store $0.00$ as a rank. This table could be either computed by the owner of the document collection and outsourced to the cloud, or computed by the cloud itself since it receives the actual document collection $D$ in the clear.

Now suppose that a user wants to query the cloud for the multi-keyword query "searchable encryption". Then, the cloud first searches for the terms "searchable" and "encryption" in the table, adds the corresponding rows together to get the overall score of the query, sorts the scores, and returns the relevant documents in a sorted order.

Ranking search results on encrypted data

A user that wishes to protect her privacy is likely to outsource her document collection to the cloud in an encrypted format: $E(D_1),\dots,E(D_n)$. In order to be able to perform ranked search, the user has to create the rank table $T$ and send it to the cloud (as opposed to outsourcing plaintext data where the cloud could also compute the rank table itself). Since the rank table contains information about the distribution of words in individual documents and the whole collection, it has to be encrypted as well. However, in order for the server to be able to return ranked results using the $\mbox{tf-idf}$ method described above, encrypted$T$ should be able to support the following operations:

- search for terms/keywords

- add numerical values

- sort a list of numerical values.

For the first operation one could simply encrypt the keywords on the table using a searchable encryption (SE) scheme. Then, whenever the user wants to search for a phrase, she sends to the cloud an SE trapdoor for each keyword in the phrase. The server can then use the trapdoors to locate the keywords in the table.

The next two operations refer to the numerical entries on the table which should be encrypted in a way that supports addition and sorting. A natural solution would be to encrypt these values under a fully-homomorphic encryption scheme that can support any type of computation over encrypted data. However, the resulting solution would be very inefficient to be applied in practice. Another potential solution would be to encrypt the numerical values under an order-preserving encryption (OPE) scheme. However, this would be sufficient only for single-keyword queries, since OPE schemes cannot support homomorphic addition (and, even if they did, they would not be secure. Note that for single keyword queries, OPE might not be ideal since it leaks the rank order of the documents for each keyword (see also the discussion here.

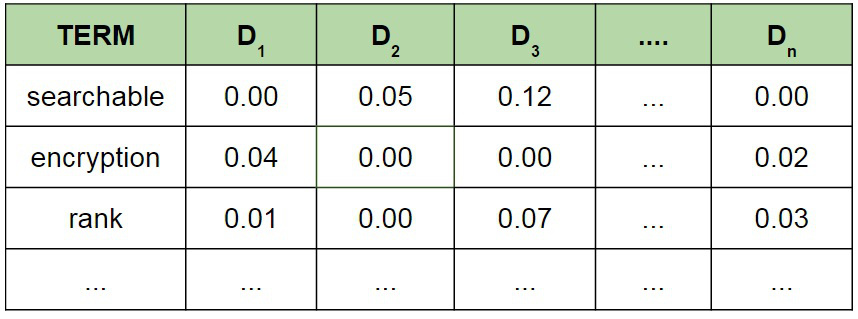

Given that we aim for an efficient and provably secure solution, we propose to encrypt the numerical values of the rank table using the Paillier encryption scheme: a semi-homomorphic scheme that supports the addition of encrypted values. (For the rest of this post, we use $[a]$ to denote the encryption of value $a$ using this scheme.) %a semi-homomorphic encryption scheme. By the properties of Paillier, the server can add the corresponding rows of $T$ when a query is received. What is still left to discuss is, how the server can also sort these encrypted values. In the rest of the post, we describe our private sorting mechanism over encrypted values.

Our private sorting mechanism requires to equip the cloud server with a secure co-processor (e.g., IBM PCIe, Intel SGX, Windows TPM. The secure co-processor is then given the decryption key of the semi-homomorphic encryption scheme which lets him assist the cloud server in sorting. For the protocol to proceed, we assume that the co-processor does not collude with the cloud server and both of them are following the protocol in an honest-but-curious way. That is, neither of them deviates from the protocol but both are curious to learn more about user's data.

Regarding the privacy of our scheme, we design our protocol in such a way that: (a) the co-processor learns nothing about the values being sorted and (b) the cloud server, as in SE, learns the search pattern (i.e., whether a keyword was queried before or not), but learns nothing about the ranking of the documents. For example, he does not learn which document ranks higher for user's query.

Private Sort

We now develop a sorting protocol that the cloud server and the co-processor

can use to jointly sort encrypted ranking data of the documents. From now on we

denote the cloud server by $S_1$ and the co-processor by $S_2$. Our private

sort is a two-party protocol between $S_1$ and $S_2$ where $S_1$ has an

encrypted array of $n$ elements $[A] = { [A_1], [A_2], \ldots, [A_n]}$ and

$S_2$ has the secret key that can decrypt $A$.

By the end of the protocol, $S_1$ should obtain $[B] = {[B_1],

[B_2], \ldots, [B_n]}$ where $[B]$ is an encryption of$A$ sorted. Since $S_1$

and $S_2$ are both curious, we are interested in protecting the content of $A$

and$B$ from both of them and we are willing to reveal only the size of

$A$,$n$. Hence, $S_2$ should only assist $S_1$ in sorting without seeing the

encrypted content of $A$ or $B$, otherwise he can trivially decrypt it. On the

other side of the protocol, nothing about the decryption key nor plaintext

values of $A$ and $B$ should be leaked to $S_1$. For example, we do not want

to leak to neither $S_1$ nor $S_2$ values of elements in $A$, their comparison

result with other elements, and their new location in $B$ (in the paper we

express these properties using simulation based security definitions).

Private Sort Construction Overview. As can be seen from the definitions, the participation of $S_1$ and $S_2$ in private sort should not reveal anything about the content of the data to either of them. Hence, any method we use for comparison and sorting must appear independent of the data. We note, however, that many sorting algorithms access the data depending on the comparison result and data content (e.g., quicksort). This does not fit our model where everything about the data, including individual comparisons, should be protected from $S_1$ and $S_2$.

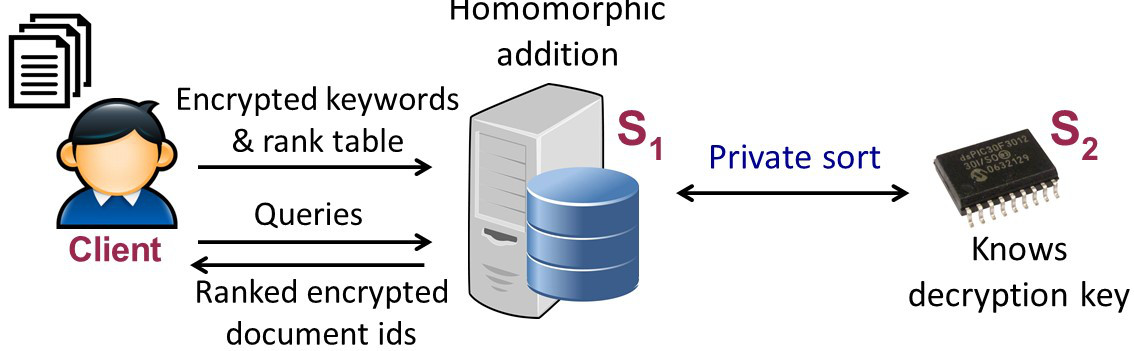

Fortunately, there are sorting algorithms where data comparisons are determined by the size of the data to be sorted, $n$ in our case, and not the data content. One such algorithm is a sorting network by K. Batcher which relies on Two-Element Sort circuit. This circuit takes two elements and outputs them in a sorted order. Then the network consists of $O(\log n)$ layers where every layer has $O(n)$ Two-Element Sort circuits, where constants in big-O are determined by $n$. In order to sort the data, one simply passes it through the network. Moving the data through the network depends only on $n$ and the Two-Element Sort. Hence, if we develop a private Two-Element Sort, the implementation of private Batcher's network becomes trivial.

Private Two-Element Sort

As the name suggests, Private Two-Element Sort is a special case of Private Sort, as defined above, for the case $n=2$. That is, $S_1$ has two encrypted elements $[a]$ and $[b]$ and wishes to obtain $[c]$ and $[d]$ where $c = \min(a,b)$ and $d = \max(a,b)$. Similarly,$S_2$ has the secret key of the encryption. The security definition is also the same and informally states that neither $S_1$ nor $S_2$ learn anything about $a$ and $b$.

We first describe operations that are required to perform Two-Element Private Sort without encryption and then for every operation give its private version. The sorting consists of:

- $t := a > b$ (Set bit $t$ to the result of comparing $a$ and $b$).

- $c := (1-t)a + tb$ (Use $t$ to select the minimum of $a$ and $b$).

- $d := ta + (1-t)b$ (Use $t$ to select the maximum of $a$ and $b$).

Note that these three operations have to be performed on encrypted data: $a$ and $b$ are part of the encrypted input of $S_1$, bit $t$ and values $c$ and $d$ also should be encrypted to protect their content from $S_1$. Moreover, neither of these values should be shown to$S_2$ since he can trivially decrypt them, violating privacy guarantees against$S_2$.

We show how to perform above operations over encrypted data one by one, starting first with a Private Comparison protocol for computing $[t]$ and following with a Private Select protocol for computing $[c]$ and $[d]$.

Private Comparison. This protocol is a variation of a classical Andrew Yao's Millionaire's problem: $S_1$ has $[a]$ and $[b]$ and wishes to obtain $[t]$, where $t = (a > b)$ and $S_2$ has the private key of the encryption scheme. Although there is more than one way of doing so, we pick an efficient algorithm from a recent result by Bost et al., which is a correction of the original protocol by T.Veugen. This algorithm lets $S_1$ and $S_2$ compare $a$ and $b$ using number of interactions that is logarithmic in the number of bits in each element.

Note that neither $S_1$ nor $S_2$ learn the values of $a$, $b$, and $t$. In addition, $S_2$ does not learn the ciphertexts corresponding to these values.

Private Select. Given the comparison bit $t$, we now devise a private algorithm for using this bit to select the minimum and the maximum value of $a$ and $b$ (that is performing operations 2 and 3 above). Recall that $S_1$ has to obtain $[c]$ and $[d]$ with $S_2$ "blindly" assisting him in the protocol.

We wish to use simple cryptographic operations in order to compute $c$ and $d$. That is, we use semi-homomorphic cryptographic techniques as opposed to fully-homomorphic ones. To this end, we use an interesting property of layered Paillier Encryption. We omit many details from here and only point out the features that we need.

We denote messages encrypted using first and second layers of Paillier Encryption as $[m]$ and $[![m]!]$, respectively. We recall that Paillier Encryption supports addition of ciphertexts as well as multiplication by a constant, i.e., $[m_1][m_2] = [m_1+m_2]$ and $[m]^{C} = [Cm]$. The same operations hold for ciphertexts of the second layer. However, what is more interesting is that the ciphertext of the first layer is in the same domain as the plaintext of the second layer, which allows the following operations:

This trick allows us to implement the functionality of private select for $c$, and similarly for $d$, as follows:

\[[\![[c]]\!] := [\![[a]]\!]^{[1-t]} [\![[b]]\!]^{[t]} = [\![[(1-t)a + tb]]\!]\,\]

where $c$ and $d$ are doubly encrypted.

Recall that the output of Two-Element Private Sort is a building block of the general sort, where $c$ and $d$ participate in further invocations of Two-Element Private Sort. To make the values $c$ and $d$ usable in the next layer of Batcher's network, $S_1$ uses $S_2$ to strip off the extra layer of encryption. $S_1$ blinds the value he needs to strip via $[![[c+r]]!]$, and sends it to $S_2$, who decrypts the ciphertext and sends back only $[c+r]$. Using homomorphic properties of Paillier, $S_1$ subtracts $r$ to get $[c]$. The similar protocol is executed for $d$. %Note that this protocol requires one interaction with $S_2$.

Private $n$-Element Sort

Let us now show how to sort an array of $n$ elements using our Private Two-Element Sort. %We are now ready to combine all the building blocks. $S_1$ executes Batcher's sorting network layer by layer. For each layer in the network and for every sorting gate in this layer, he engages with $S_2$ in Private Two-Element Sort. He uses the outputs of this layer as inputs to the next layer of the network. (See Figure\ref{fig:batcher} for an illustration.)

![Example of privately sorting an encrypted array of four elements $5,1,2,9$ where $[m]$ denotes a Paillier encryption of message $m$ and $\mathsf{pairs}_i$ denotes a pair of elements to be sorted. Note that only $S_1$ stores values in the arrays $A_i$ while $S_2$ blindly assists $S_1$ in sorting the values.](../../img/batcher1.jpg)

Sketch of Privacy Analysis. We note that the number of times $S_1$ engages with $S_2$ in the protocol does not reveal either of them anything about the data content. Each engagement is an execution of Private Two-Element Sort which, in turn, is a call to Private Comparison and two calls to Private Select. Private comparison guarantees privacy against $S_1$ and $S_2$ as long as they are non-colluding honest adversaries. Private select relies on homomorphic properties of Paillier and requires only the re-encryption step from $S_2$. Since $S_2$ receives a blinded value he does not learn the value of $c$ or $d$. Moreover, since the values of $c$ and $d$ are re-randomized we can treat $O(n (\log n)^2)$ calls to Two-Element Private Sort independently.

Conclusion

We constructed a private sort mechanism that allows a cloud server $S_1$ to sort a list of encrypted data without learning anything about their order (while assisted by a non-colluding co-processor $S_2$). As discussed in the beginning of our post, this tool lets a user store his encrypted documents in a cloud server and receive ranked results when searching on them.

The method, as described in the post, assumes that the rank table has an entry for every keyword-document pair, even if a keyword does not appear in this document zero is stored. In the full version of the paper, we show that we can relax this requirement and store only information for documents where keyword appears, hence, significantly reducing the size of $T$ and query time for the server. If we do so, we can add ranking to the optimal SE technique by Curtmola et al. for single keyword queries or to the technique by Cash et al. for efficiently answering Boolean queries on encrypted data (see earlier blog post for more details on each). Although the resulting scheme gives a significant performance improvement and protects the ranking of the documents, it inherits the leakage of the access pattern (i.e., identifiers of the documents where each query keyword appears) from the corresponding SE technique.

Our work leaves several interesting open questions, including: how to efficiently update the collection? how can a user verify the ranking result it receives? is a non-colluding co-processor provably necessary to solve multi-keyword ranked search? Any ideas? :)